Being raised under strict religious doctrine can have knock-on effects that impact all parts of life, particularly parenting, says Dr Cathy Kezelman, president of Blue Knot Foundation, an organisation that provides information and support to those suffering complex trauma. “When you’ve been raised within a controlled environment with very little freedom to make your own choices or realise that you can make choices,” she says, “it’s very difficult to develop the strong core sense of self necessary to provide your children with a secure base from which they can explore the world.”

According to Kezelman, healing begins by making sense of what has happened, how it affected you, learning self-compassion and re-evaluating your upbringing through parenting your own children. “Ways to achieve this can include counselling, self-care, meditation, yoga and art therapy. All can help to soothe the nervous system, build a sense of safety and trust and, as a parent, gradually enable your children to develop a sense of security and autonomy.”

Here, three women who have left their religion share their experiences.

“Parenting has been a healing experience”

Laura McConnell Conti, 43, was a fifth-generation member of a strict fundamentalist Christian sect. Because she suffers from complex post-traumatic stress disorder, the responsibility of parenting falls on her child’s father.

“From age 12, I helped to raise my siblings. I was the eldest girl and that was what was expected of me because of our religious community’s gendered beliefs. Daily, I had to prepare their clothes, get them ready for school, help them with their homework. On the weekends I had to ensure they attended church events wearing the right dresses and having their hair in the right style. Overall, I had to keep their behaviour in line with our religious beliefs and this left me exhausted.

Wanting something different for my life, I left the church at 19. Once I got an education and a well-paying job, I was able to afford therapy. Subsequently, I spent my late 20s and 30s recovering from complex trauma – a consequence of having to worry about and care for others when I was a child myself.

At first, I didn’t want to have children. I didn’t feel I was maternal like other women seem to be, or that I had the capacity to raise a child without it impacting my health.

Eventually, I met with someone who understood that the only way I could have a child was if he was the primary carer, and I had a son in my late 30s.

I didn’t think my life would change very much, but the reality is that parenting has been a healing experience for my own childhood trauma – although that was not the intention or the expectation.

My parenting style is hands-off. I don’t have the capacity to worry or organise for my son. Difficult things, like going to the doctor or getting vaccinations, I leave to his father. I get to do more of the fun stuff – clothes shopping, hanging out and playing.

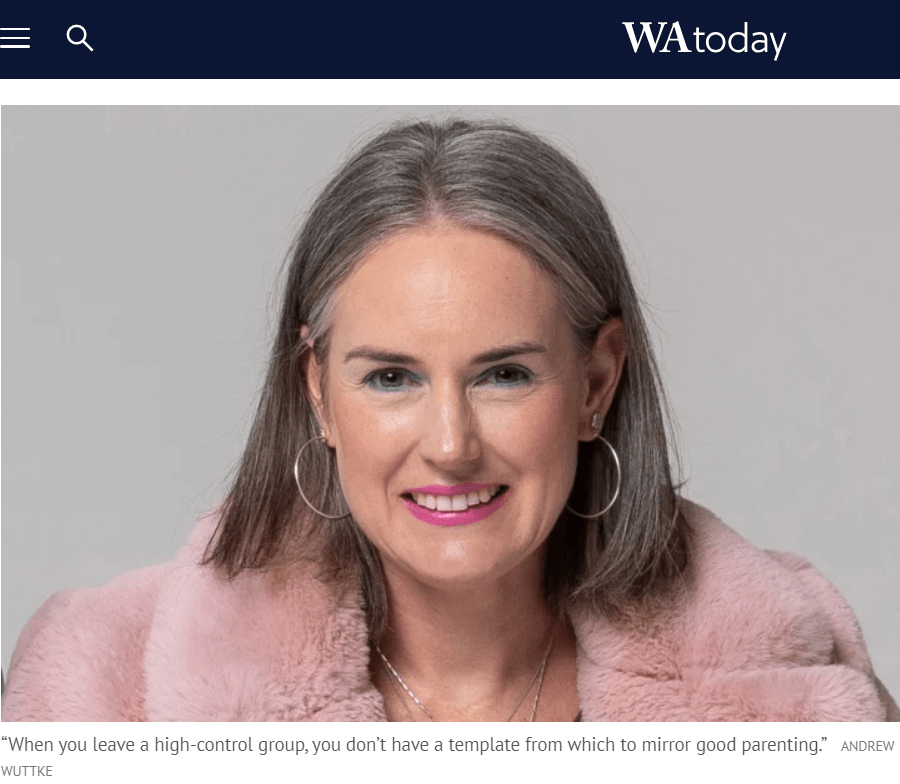

When you leave a high-control group, you don’t have a template from which to mirror good parenting. You’re relearning to do things in a very different way and, as a result, I find parenting to be a lonely experience.

And due to the abuses I experienced, I’m hyper-vigilant. This means my son hears and learns about personal safety and consent at a much younger age than most. In turn, during periods when I’m not feeling well, he understands that I can’t be completely present in his life.

I aim to raise a well-rounded human being, who can identify safe people, has the ability to be confident in life and is surrounded by good friends, so he won’t need to fill his voids from such groups.”

“The backlash from the parish was shocking”

Mel Welch, 41, was born and raised under strict religious doctrine. When she left the church, she was overprotective of her children. She has since learnt that instilling self-trust is the best way to empower them.

“There were lots of rules and heavy control under the religious group I was raised in. The biggest fear instilled in me was of going to hell. It was deeply ingrained that if I upset anyone or did anything wrong, that would upset God and I would be banished to hell automatically. So I made sure not to upset the pastors or my parents.

I married a pastor’s son when I was 18 and he was 20. Marriage was the only way that being alone together would be allowed by the pastors.

Sadly, my first-born child died at birth. The backlash from the members of the parish was shocking: some said my baby’s death was because we didn’t pray enough. We were consequently given six weeks to get over our grief.

I went on to have four more children and by the time I turned 30, I could no longer keep up with the pressure I was putting on myself to attend weekly church gatherings and Sunday service. Feeling that no matter what I did I would never be enough, one Sunday afternoon in 2012 I sat opposite my husband and said, ‘I’m no longer attending church.’ My body felt nauseous from the anxiety of even hearing me say that and my husband turned white. That goes to show just how much power they had over our lives.

Consequently, I was shunned by the community. Gradually, my husband came to his own realisation and conclusion about the church and followed me six months later.

During this time, I continued to read the Bible on my own. The more I did, the more I started to listen to and trust my intuition about what the teachings meant. This is a new God, I realised. I slowly understood that I wasn’t going to die because I’d left the church. It was all a lie, so I started to wonder what else wasn’t true.

There was definitely a long transition period around figuring out how to raise my kids, because I was relearning so much and essentially becoming an adult myself. Until I was able to discern the lies from the truths, I became overprotective of them, a form of helicopter parenting, especially around any sort of religious ideas or strict ideals.

Over time, I realised that self-trust is necessary to thrive. I’ve taught my children to create a personal relationship with God through reading the Bible on their own, a relationship that’s based on self-awareness and confidence in their own instincts.”

“Marrying outside the church was frowned upon”

Susannah Birch, 37, was raised in a church that discouraged her from engaging in “worldly” activities. She is teaching her children how to be independent thinkers.

“One of the main teachings I was raised on is that Christians shouldn’t be ‘worldly’. This meant I wasn’t allowed to read mainstream books – by the time I was 12, I had actually read the Bible twice – watch popular movies or wear ostentatious jewellery or make-up. Sex before marriage was considered a sin. Further, being friends with or marrying anyone from outside the church group was severely frowned upon because they were considered to be ‘evil’.

My parents divorced when I was 13, by which time my family had distanced itself from the church. To my surprise, my father, who maintained more balanced religious beliefs, allowed me to do things considered worldly. I quickly discovered the Spice Girls and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and that began to change my whole world view. I also read different book genres and that made me question everything I had been taught growing up.

Subsequently, at age 20, I married a non-Christian. And when I had my two children, I intentionally introduced them early on to a wide range of fiction, music and movies so they could have a holistic view of the world.

Prior to becoming a parent, I thought I was over my indoctrination. Yet whenever my children did things the church would consider wrong or ‘sinful’, I was back in that world. I had to take conscious steps to prevent myself from imposing narrow ideas on my children. Today, whenever my children do something wrong, I try to explain to them why it’s wrong, as opposed to the punishments I received growing up, which I was never allowed to question.

My children attend a Catholic school, which I chose due to the quality of education it offers. It doesn’t bother me that they may be exposed to religious teachings, because at home we read and talk about multiple religions and philosophies, including paganism and Buddhism.

I’ve done my best to teach them to see different points of view and choose what they want to follow, after applying critical thinking. If they feel that something is true simply from emotions or peer pressure, I try to encourage them to question why and to think for themselves, not to be swayed by others’ opinions. I also want them to question the world around them and not to sit in self-criticism, as the church I grew up in taught me to do.”

蓝结基金会(Blue Knot Foundation)是一个为遭受复杂创伤的人提供信息和支持的组织,该基金会主席凯茜-凯泽尔曼(Cathy Kezelman)博士说,在严格的宗教教义下长大会产生连锁反应,影响生活的方方面面,尤其是养育子女。”她说:”当你在一个受控制的环境中长大,几乎没有自由做出自己的选择或意识到自己可以做出选择时,你就很难培养出必要的强烈的核心自我意识,从而为你的孩子提供一个可以探索世界的安全基础。

凯泽尔曼认为,治疗首先要了解发生了什么,它是如何影响你的,学会自我同情,并通过养育自己的孩子来重新评估你的成长经历。”实现这一目标的方法包括咨询、自我保健、冥想、瑜伽和艺术疗法。所有这些都可以帮助舒缓神经系统,建立安全感和信任感,作为父母,逐渐让孩子建立安全感和自主感。”

在这里,三位已经脱离宗教的女性分享了她们的经验。

“为人父母是一次治愈的经历

43 岁的劳拉-麦康奈尔-孔蒂是一个严格的原教旨主义基督教派的第五代成员。由于她患有复杂的创伤后应激障碍,养育孩子的责任就落在了孩子的父亲身上。

“从 12 岁开始,我就帮助抚养我的兄弟姐妹。我是长女,这也是我们宗教团体的性别信仰对我的期望。每天,我都要为他们准备衣服,让他们做好上学的准备,帮他们做作业。周末,我必须确保她们穿着合适的衣服、梳着合适的发型参加教会活动。总之,我必须让他们的行为符合我们的宗教信仰,这让我疲惫不堪。

为了追求不同的生活,我在 19 岁时离开了教会。当我接受教育并找到一份收入不错的工作后,我就有能力支付治疗费用了。随后,我在 20 多岁和 30 多岁时从复杂的心理创伤中恢复过来–这是我自己还是个孩子时不得不担心和照顾他人的后果。

起初,我并不想生孩子。我觉得自己不像其他女性那样具有母性,也不认为自己有能力抚养孩子而不影响自己的健康。

最后,我遇到了一个人,他理解我只有在他是主要照顾者的情况下才能要孩子,于是我在 30 多岁时有了一个儿子。

我本以为我的生活不会有太大的改变,但现实是,养育孩子治愈了我童年的创伤–尽管这并不是我的初衷或期望。

我的育儿方式是放手不管。我没有能力为儿子操心或安排事情。困难的事情,比如看医生或接种疫苗,我都交给他父亲去做。我可以做更多有趣的事情–买衣服、闲逛和玩耍。

当你离开一个高度控制的群体时,你就没有了一个可以借鉴的良好育儿模板。你要重新学习以一种截然不同的方式做事,因此,我觉得养育孩子是一种孤独的体验。

由于经历过虐待,我变得高度警惕。这意味着我的儿子在比大多数人更小的时候就听说并学会了个人安全和同意。反过来,在我不舒服的时候,他也明白我不可能完全参与他的生活。

我的目标是培养一个全面发展的人,他能识别安全的人,有能力对生活充满信心,身边有很多好朋友,这样他就不需要从这类群体中填补空缺了。”

“教区的反弹令人震惊”

41 岁的梅尔-韦尔奇是在严格的宗教教义下出生和长大的。离开教会后,她对孩子过度保护。从那时起,她明白了灌输自我信任是增强孩子能力的最好方法。

“在我成长的宗教团体中,有很多规则和严格的控制。灌输给我的最大恐惧就是下地狱。根深蒂固的观念是,如果我惹恼了任何人或做错了任何事,就会惹恼上帝,我就会被自动放逐到地狱。因此,我确保不惹牧师和父母生气。

我 18 岁时嫁给了一位牧师的儿子,当时他 20 岁。只有结婚,牧师们才会允许我们单独在一起。

不幸的是,我的第一个孩子在出生时就夭折了。教区成员的反弹令人震惊:有些人说我孩子的死是因为我们祈祷不够。因此,我们被给予六周的时间来走出悲痛。

我后来又生了四个孩子,到我 30 岁时,我再也无法承受每周参加教会聚会和主日礼拜给自己带来的压力。2012年的一个周日下午,我坐在丈夫对面说:”我不再去教堂了。听到我这么说,我的身体感到一阵恶心,而我的丈夫脸色煞白。这足以说明他们对我们的生活有多大的影响力。

因此,我受到了社区的排斥。渐渐地,我丈夫对教会有了自己的认识和结论,并在六个月后追随了我。

在此期间,我继续自己读圣经。读得越多,我就越开始倾听并相信自己对教义含义的直觉。我意识到,这是一个全新的上帝。我慢慢明白,我不会因为离开教会而死。这一切都是谎言,所以我开始思考还有什么不是真的。

在如何抚养孩子的问题上,我肯定经历了一段漫长的过渡期,因为我重新学习了很多东西,基本上自己也变成了一个成年人。在我能够辨别谎言和真相之前,我变得过度保护他们,这是一种 “直升机养育”,尤其是在任何宗教观念或严格的理想方面。

随着时间的推移,我意识到自我信任是茁壮成长的必要条件。我教孩子们通过自己阅读《圣经》与上帝建立个人关系,这种关系建立在自我意识和对自己直觉的自信之上。

“在教会外结婚是不被允许的”

37 岁的苏珊娜-伯奇(Susannah Birch)从小生活在一个不鼓励她参与 “世俗 “活动的教会。她正在教孩子们如何成为独立的思考者。

“我从小接受的主要教导之一就是基督徒不应该’世俗’。这意味着我不能阅读主流书籍(12 岁时,我实际上已经读了两遍《圣经》),不能看流行电影,也不能佩戴浮夸的首饰或化妆。婚前性行为被认为是一种罪过。此外,与教会以外的人做朋友或结婚都会受到严厉的指责,因为他们被认为是 “邪恶 “的。

我的父母在我 13 岁时离婚了,那时我的家庭已经远离了教会。令我惊讶的是,我的父亲在宗教信仰上比较平衡,他允许我做一些被认为是世俗的事情。我很快就发现了辣妹和吸血鬼猎人巴菲,这开始改变了我的整个世界观。我还阅读了不同类型的书籍,这让我对从小到大所受的一切教育产生了质疑。

随后,20 岁那年,我嫁给了一个非基督徒。有了两个孩子后,我有意让他们尽早接触各种小说、音乐和电影,让他们对世界有一个全面的认识。

在为人父母之前,我以为自己已经摆脱了被灌输的观念。然而,每当我的孩子们做了教会认为错误或 “有罪 “的事情时,我就又回到了那个世界。我不得不有意识地采取措施,防止自己把狭隘的想法强加给孩子。如今,每当我的孩子做错事时,我都会试着向他们解释为什么这样做是错的,而不是像我在成长过程中受到的惩罚那样,从不允许我提出质疑。

我的孩子们就读于一所天主教学校,我选择这所学校是因为它的教育质量。我并不担心他们会接触到宗教教义,因为在家里我们会阅读和谈论多种宗教和哲学,包括异教和佛教。

我尽我所能教他们看到不同的观点,并在运用批判性思维后选择他们想要遵循的观点。如果他们仅仅因为情绪或同伴的压力而认为某件事情是正确的,我会尽量鼓励他们质疑原因并自己思考,而不是被他人的观点所左右。我还希望他们质疑周围的世界,而不是像我成长的教会教导我的那样,坐在自我批判中”。